Day One at Retromobile 2026: BMW Turns Le Mans Into a Pop-Up Art Museum

BMW 3.0 CSL Art Car (Frank Stella, 1976) - Life in Classic

On the first day at Retromobile 2026, the BMW area doesn’t read like a brand stand in the usual sense. It reads like a curated gallery that happens to use race cars as its canvases. The concept is simple and strong: for the show’s 50th anniversary, Retromobile hosts a reunion of the seven BMW Art Cars that actually raced at the 24 Hours of Le Mans. BMW and the organisers frame the display as a “legendary garage,” but the execution lands closer to a museum installation, with clean platforms, large-format artist panels, and moving images that keep pulling your eye back to the cars.

The official timing matters because it shapes the energy in the hall. Retromobile runs from 28 January to 1 February at Paris Expo Porte de Versailles, and day one always carries that mix of anticipation and orientation. People still learn the layout, and photographers still test angles. BMW’s display feels built for that opening-day attention, yet it also rewards the slower visitor who comes back later and starts reading the walls.

The “Legendary Garage” That Works Like a Timeline

BMW’s own press release lays out the full set of cars on display in Paris: the BMW 3.0 CSL by Alexander Calder (1975), the BMW 3.0 CSL by Frank Stella (1976), the BMW 320i Turbo by Roy Lichtenstein (1977), the BMW M1 by Andy Warhol (1979), the BMW V12 LMR by Jenny Holzer (1999), the BMW M3 GT2 by Jeff Koons (2010), and the BMW M Hybrid V8 by Julie Mehretu (2024).

Your photos capture that arc perfectly, because they show how the idea evolves from era to era. The early cars use the body as a bold surface. The later cars use the body as a message. By the time you reach the newest prototype, the “paint” starts to behave like motion itself.

Calder’s 3.0 CSL: The Car That Sets the Tone

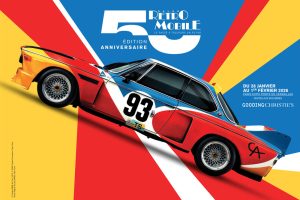

If one car anchors the whole room, it’s the 1975 3.0 CSL Art Car. Retromobile even used the Calder CSL as the icon for the 50th anniversary poster, which tells you how central this car is to the story they want visitors to take home.

In person, what stands out is how “clean” the idea feels. The forms look playful, but they also look deliberate. It doesn’t try to hide that this is a race car; it frames the race car as something joyful. In your photo, the CSL sits on a rotating platform, with archival visuals on the wall behind it. That staging makes a difference. It turns the car into a reference point, the start of the line. You feel the collection begin there, not in a brochure, but in physical space.

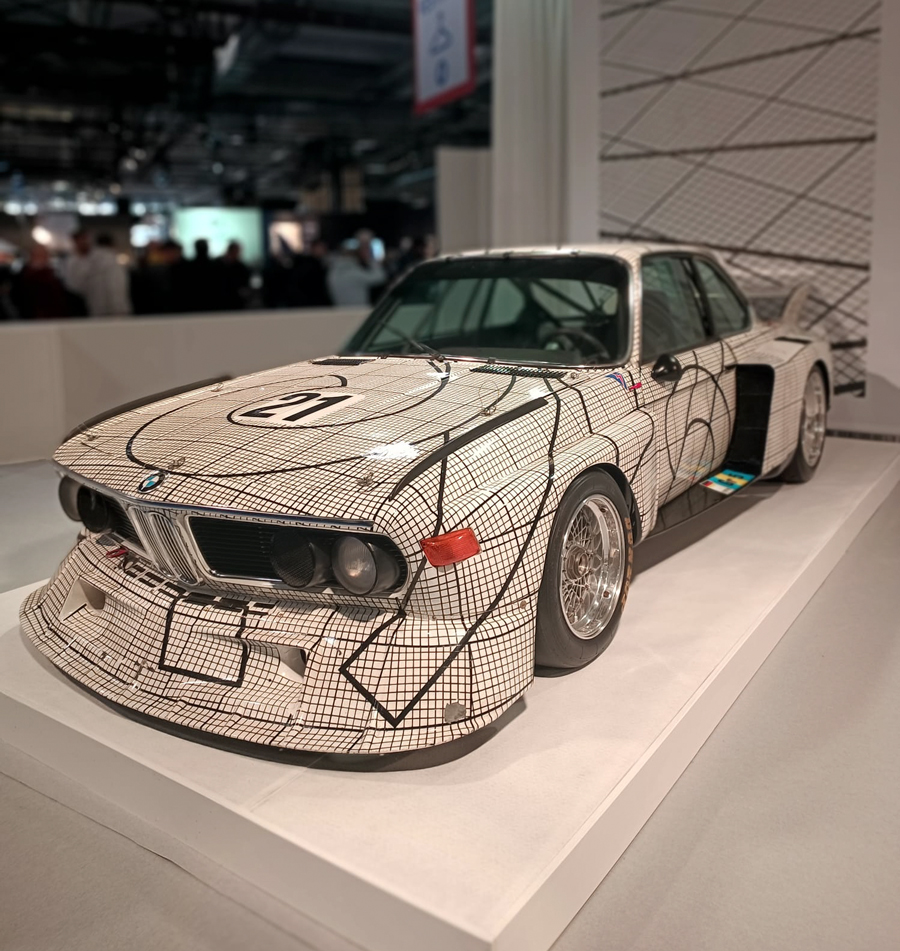

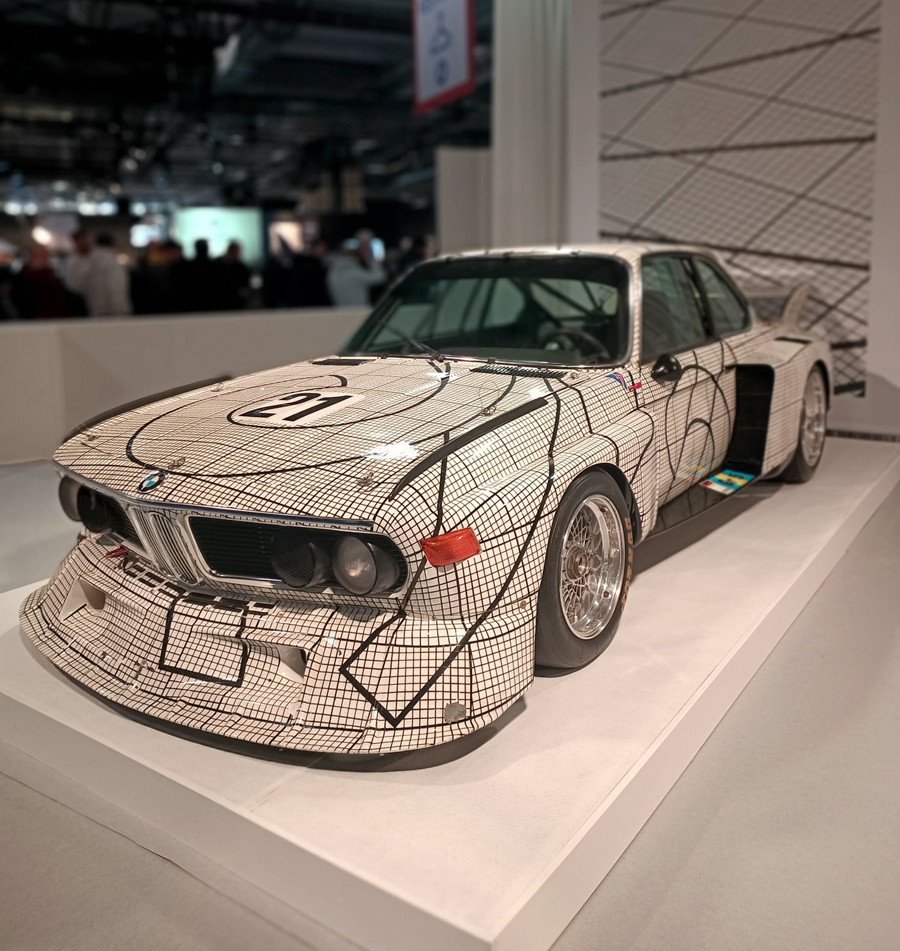

Stella’s Graph Paper CSL: When Art Starts Talking to Engineering

The 1976 3.0 CSL by Frank Stella changes the mood. Your image shows the famous grid treatment, which looks almost like a draughtsman’s sketch laid over the bodywork. It feels analytical, even a little obsessive, and that fits the CSL as an engineering object.

This is where the stand’s “garage” idea starts to click. A garage is where people measure, test, and rethink. Stella’s CSL looks like someone brought the measuring process out onto the paint. It makes the car feel like a technical drawing that escaped into three dimensions.

Lichtenstein’s 320i Turbo: A Pop-Art Landscape at Speed

The 1977 BMW 320i Turbo by Roy Lichtenstein brings the pop vocabulary into motorsport. In your photo, the car’s dotted patterns and sweeping lines read immediately, even before you spot the artist credit on the wall panel behind it. The piece feels like a moving landscape, with motion implied by graphic rhythm rather than by realism.

This is also where you start noticing how American the artist roster feels in this specific Le Mans subset. Calder, Stella, Lichtenstein, Warhol, Holzer, and Koons all connect the collection to American modern art, while the setting stays distinctly European: Paris, Retromobile, and the long endurance mythology of Le Mans.

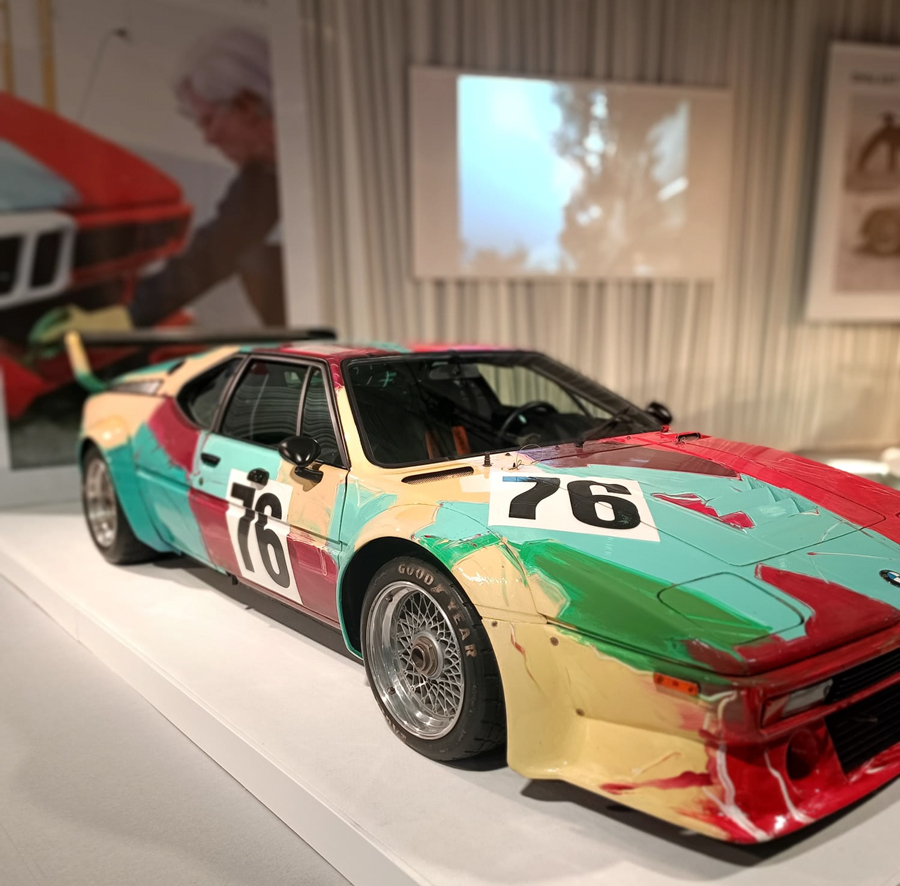

Warhol’s M1: The Most Human Moment in the Room

Warhol’s BMW M1 sits in your images with race number 76, and the car still carries the energy that made it famous. Warhol approached the body like a fast painting, not a perfect one. That matters because it injects a kind of humanity into a world that often chases perfection.

The display reinforces that point. You have a large panel behind the car, and the visuals in the room keep reminding you that these cars didn’t exist to sit still. They existed to run, and sometimes to suffer. Warhol’s M1 holds that tension well. It looks like art, but it also looks like it wants to get back on track.

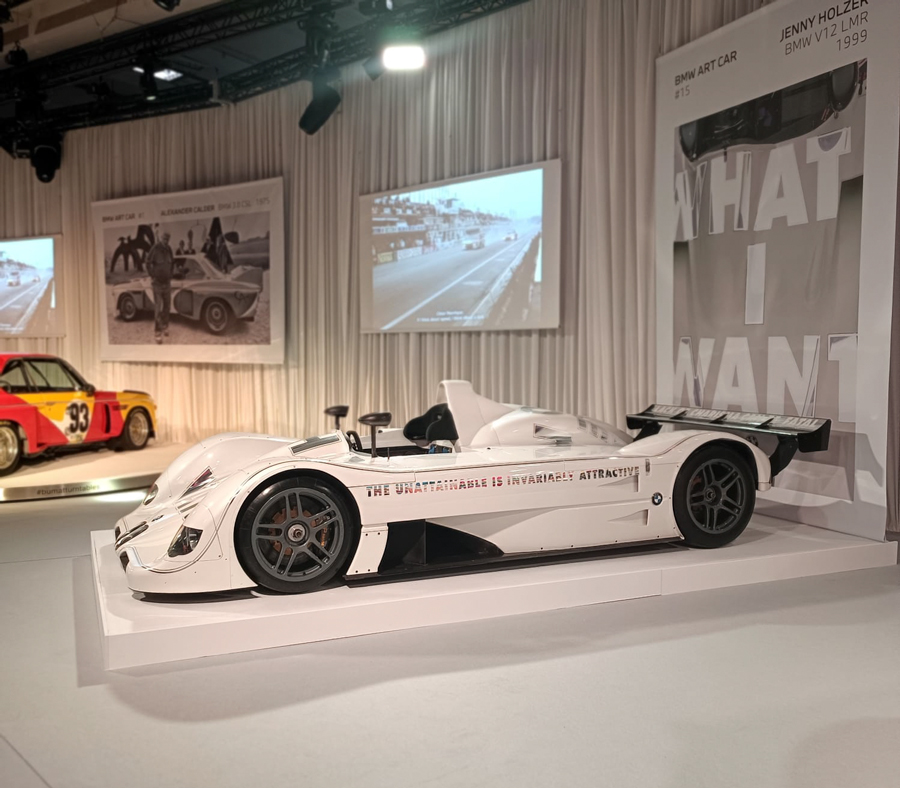

Holzer’s V12 LMR: Text as Livery, Message as Aerodynamics

Then the stand jumps to 1999 with Jenny Holzer’s BMW V12 LMR, and the vibe shifts again. In your photo, the car sits low and long, finished in white, with bold text along the flanks. The wall panel behind it carries the same “WHAT I WANT” language, which makes the whole corner feel like an installation rather than a display.

This car shows how the Art Car idea matured. It no longer depends on pattern alone. It depends on language. It turns the race car into a moving billboard for a statement, but it keeps the statement ambiguous enough to stay art, not advertising.

Koons’ M3 GT2: Color That Pulls You Forward

Koons’ M3 GT2 is the stand’s pure adrenaline hit. Your photo shows the car with the number 79 and the unmistakable stripes rushing toward the nose. Retromobile’s own editorial explains that Koons designed the car to suggest speed through converging lines and bright colour, and that BMW ran the car at Le Mans in 2010.

In person, the stripes do something clever. They don’t only decorate the surface. They guide how you look at the shape. They pull your gaze forward, which makes the car feel like it’s already accelerating, even on a static platform. It’s an effect you can’t fully get from a single photo, because your eye keeps moving while you stand there.

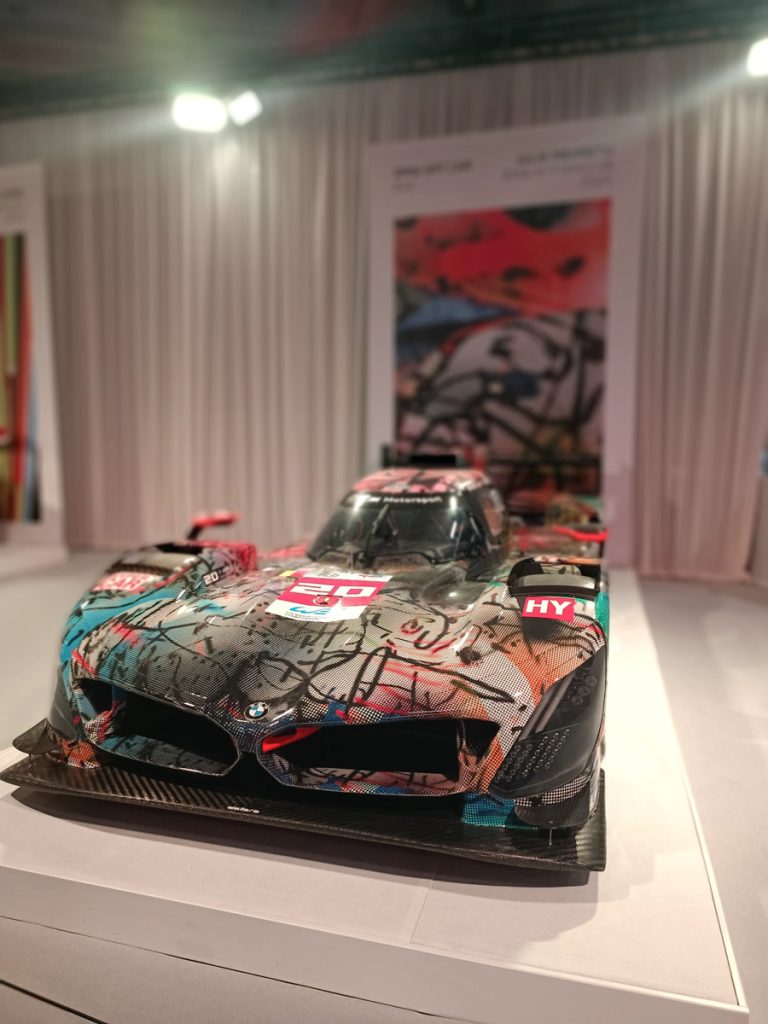

Mehretu’s M Hybrid V8: The Present Tense of Endurance Racing

The newest car in your set is the M Hybrid V8 Art Car by Julie Mehretu. It looks modern in the blunt, purposeful way that current top-class endurance prototypes look modern. Yet the livery makes it feel alive, with layered marks that read like a painting in motion.

Retromobile’s official feature page adds key context: BMW commissioned Mehretu for its return to the top class of endurance racing in 2024, and the car carried number 20. The same source notes the car retired at Le Mans after 96 laps. That detail matters because it keeps the story grounded. This is not a “tribute” livery applied to a static showpiece. It’s a racing object that entered the real fight.

Why This Stand Feels Like a Statement at Retromobile

Retromobile usually offers an intoxicating mix of commerce and heritage. Dealers bring blue-chip inventory. Restorers show craftsmanship. Clubs bring community. BMW’s Art Car space plays a different role. It argues that motorsport history belongs in the same conversation as art history, and it does so without forcing the point.

BMW also chose a smart framing for a crowd that includes both experts and casual visitors. You don’t need to know chassis numbers to understand what you’re seeing. The wall panels give you the artist, the model, and the year. The visuals give you the racing context. The cars do the rest.

If you want a single takeaway from day one, it’s that this stand sets a tone for the whole anniversary edition. Retromobile’s programme leans into culture this year, and the BMW Art Cars make that direction feel real, not symbolic.

Tomorrow, we’ll stay on that same cultural thread, but we’ll shift perspective. We’ll look at how the show balances art-driven storytelling with the classic Retromobile essentials: the market, the metal, and the moments that only happen when a lot of rare objects share the same building.