From McQueen to McBean Rethinking Cool

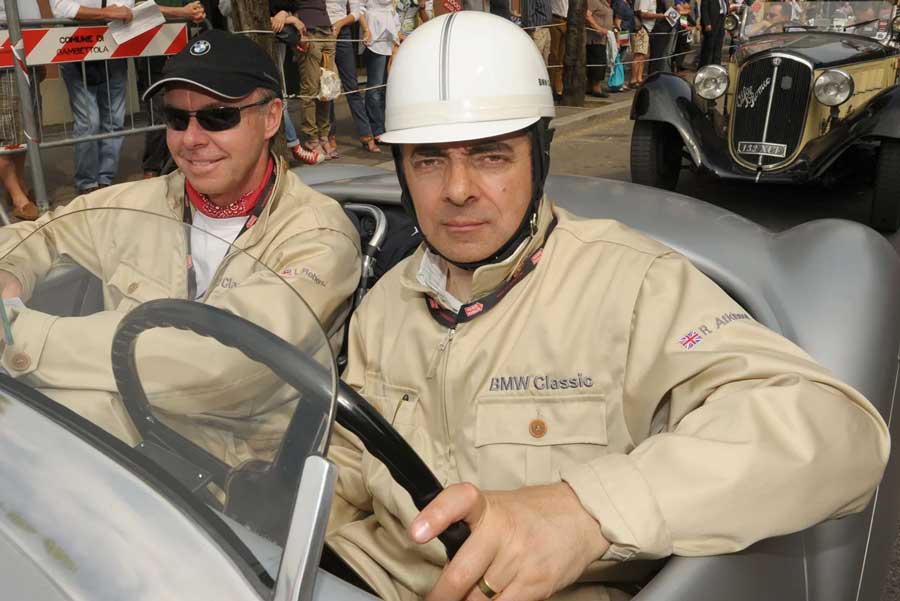

Rowan Atkinson at Life in Classic

For generations of enthusiasts, Steve McQueen has stood as the archetype of automotive cool: a bona fide star who didn’t just pose next to machines but drove them, raced them, and understood them. His allure was never only about looks or fame; it was about authenticity. McQueen’s era—the roiling, high-velocity 1960s—was a time when culture, technology, and personal expression all seemed to find a higher gear. He earned the “King of Cool” moniker in a decade crowded with contenders, from Michael Caine to Robert Mitchum. Plenty of actors projected cool, but fewer lived it at speed. James Dean and Paul Newman did, and with McQueen they formed a rare club: leading men whose passion for cars and racing was as real as the roles that made them famous.

So who carries that torch today? The answer may be more surprising than the question suggests. Consider Rowan Atkinson. To many, he’s forever Mr. Bean—hapless, wordless, profoundly uncool. But away from the elastic facial expressions and sly sight gags lies a very different figure: a committed enthusiast with an expansive, hands-on relationship with cars and motorsport.

One gateway into that world is Handy Bean, a series of bite-size, first-person “how-to” clips that reimagine the Mr. Bean persona as a pair of deft hands solving everyday problems. The format is simple and modern—more YouTube bench-top than cinematic chase scene—and yet it subtly underscores the same impulse that drew McQueen to track days and desert roads. It’s the itch to tinker, to master technique, to try and try again until skill replaces luck. In a culture saturated with image, there’s something quietly thrilling about a star who shows his work.

Atkinson’s résumé in the automotive sphere is serious, and it predates internet shorts by decades. He has owned some of the world’s most coveted road cars and, crucially, put them to the use they were built for. He has also raced a wide variety of machines, not as a one-off publicity stunt but as a committed participant. That willingness to test the limits—and sometimes pay the price—is part of what made McQueen resonate beyond Hollywood. A hero who never risks a scratch starts to look like a mannequin. Atkinson, like McQueen before him, accepts that speed and fallibility are part of the same family.

Of course, the comparison isn’t about look-alike charisma. Atkinson doesn’t fit the classic leading-man mold in the way McQueen, Dean, or Newman did, and the Bean character is practically a parody of cool. Yet that contrast is precisely what makes the case compelling. Cool has never been just a posture; it’s the composed confidence of someone fully engaged with a craft. In motorsport terms, it’s taking the right line through a corner not because a camera is rolling, but because that line is the fastest, cleanest way through.

The shape of fame has changed since the 1960s, and so has the way automotive passion is expressed. McQueen came alive in a world of grainy film stock and analog risk; today, enthusiasm often reveals itself in short-form videos, technical explainer clips, and a digital trail of pit-lane weekends. Yet the core ingredients remain: curiosity, repetition, tactile expertise, and the joy of mechanical connection. When you strip away the noise, both McQueen and Atkinson are defined by the same impulse to participate rather than merely observe.

There’s also a democratic charm in Atkinson’s approach. Handy Bean’s quiet, practical inventiveness mirrors what millions of enthusiasts do every day: improvising tools, making do with what’s at hand, and finding elegant solutions to stubborn problems. That accessible spirit may be the most modern form of cool—less about marble statues and more about shared skills. And unlike the aloof mystique that often surrounds mid-century icons, Atkinson’s public persona invites a smile. He reminds us that joy and seriousness can coexist; you can be deeply committed and still laugh at yourself.

So if the question is who might wear the crown today, one candidate stands out for reasons that are both unexpected and refreshingly down-to-earth. Rowan Atkinson isn’t trying to be Steve McQueen, and that’s the point. He has carved his own lane: performer, enthusiast, racer, tinkerer. In a world that prizes polish, he offers something sturdier—proof that love for machines, practiced skill, and an appetite for learning can be as magnetic as any poster-boy image. Call it a different kind of royalty. Call it Steve McBean.